Donkey Kong Bananza: Accessibility Review

I am probably not the right expert to review Donkey Kong Bananza. Sure, like most 90s kids I grew up around Mario and Crash and Spyro, but I haven’t stuck with 3D platformers much as an adult. In the past decade, the only two 3D platformers I beat were Astro’s Playroom and Spyro Reignited. (Which yes, is me admitting I didn’t play all the way through Mario Odyssey and I haven’t even touched GOTY winner Astro Bot.)

BUT – even though 90% of my platforming experience as an adult comes from Metroidvanias along with some indie 2D platformers and that one section in a JRPG that makes you question the devs’ sanity and sense of humor – I am uniquely poised to answer one essential question that will make this review unlike any other you’ll read for Bananza.

And that question is so much more than just, “Is Bananza an accessible video game?”

No, I dare to go further, to embody the spirit of DK and dig deeper. I dare to ask:

“Is Bananza accessible enough that even my non-gaming Boomer mom can play it?”

If you want to find out the answer to that question and everything else I have to say about Bananza’s accessibility, then you’ll want to keep reading.

For starters, let’s cut to the chase with my TLDR thesis about how I view Donkey Kong Bananza’s overall accessibility:

Donkey Kong Bananza is a game with largely accessible design. Its simple core mechanics, visual design language, and almost unprecedented levels of player freedom stem from a time-tested Nintendo approach of inviting play for all ages. But while this lends itself to natively accessible design, the game still lacks many key accessibility options – options that can make a crucial difference between enabling play for all ages and enabling play for all players, regardless of their visual, audio, mechanical, or cognitive needs.

Let’s unpack what I mean by that.

Accessible by Design

Ever since the days when Mario first walked forward, jumped up, broke a block with his head and a coin popped out, Nintendo have been the masters of teaching players how to play with little to no written instruction.

It’s a wordless tutorial-ization that speaks to a “family friendly” design philosophy that enables play for all ages and skill levels. Even if you’re not old enough to have strong reading comprehension, you can learn to navigate a lot of Nintendo’s first party games – especially their mascot titles and platformers.

It’s a very seamless and intuitive style of teaching. It gives you a basic tool set and lets you experiment with it in carefully crafted levels that are built around those tools and the possibilities they create. Like with the Mario jumping and block breaking example, the behaviors are repeatable and incentivized with rewards – again giving wordless feedback telling the player that they’re on the right track.

Since time immemorial, kids have learned by playing – and Nintendo games have always understood that core foundation. The player experience is tactile and rewards experimental play. You simply learn by touch – and if you try the right things, you’ll make progress or get an item.

Donkey Kong Bananza very much inherits this design philosophy and even cranks it up to 11. The game gives you a complete tool set from moment zero. Even if the in-game tutorial moment for when you “should” learn how to use a skill hasn’t popped up yet, you can still use DK’s entire essential move set from the jump (pun intended).

You are let loose in a virtual toybox and invited to experiment. You can punch forward, up, down. You can jump and even jump + punch. You can grab and tear and swing and smash and even sing – all before the game tells you that you can do any of that. Just press buttons and find out. See what you can do.

Want to follow the nice yellow objective marker? Sure, go ahead. Want to smash through a wall and go backwards away from it? Also go ahead – and here’s a bunch of gold and bananas for your trouble.

But then when you do follow the intended forward path, basic tutorials do pop up – both with a quick textual descriptor to tell you what certain buttons do and a picture-in-picture tutorial video in the bottom right corner. Again, minimal reading required. Doesn’t matter if you’re a kid or a foreign language speaker or have low vision in general – there are both worded and wordless ways to learn.

Bananza is not the kind of game where you can expect a tutorial screen to pop up with a full written explanation you need to read through – let alone the kind of game where those screens make you scroll through multiple pages of instructions (I say this as someone who mainly plays JRPGs where even basic tutorials are 3 pages long).

That said, the tutorials in the game aren’t perfect and do leave some things to be desired. For example, some of the game’s more hidden mechanics like how to find the photo mode or the DK Artist mini game aren’t explicitly mentioned by tutorial NPCs until the second half of the game which is a bit late in my opinion. But clearly, Nintendo deprioritized those (for better or worse) since they aren’t essential mechanics for gameplay progression.

Overall, the Nintendo approach to player onboarding in Bananza and beyond can be summarized as understanding the Power of Play. Let the player learn by doing. Give them the tools, and the sandbox in which to use them.

It’s a deceptively tricky thing to execute as masterfully as Nintendo do time and time again – especially in a game like Bananza where the levels need to support such a high level of destruction and chaos. But before I delve any deeper into that particular point, I want to pause here and challenge my own thesis.

Is the Bananza new player experience really as accessible as I say it is? Can anyone learn it, despite their age or skill level or ability to read a bunch of small text, etc.?

To see if my assessment actually holds up, I decided to put it to the ultimate test – by passing the controller to my mom.

Is Bananza Momma Maude-proof?

For those of you who don’t know, my mom is NOT a gamer. But to try and connect with her a bit more this year, as well as to show her some moments of fun and joy that she might not otherwise experience, I’ve slowly been trying to change that.

She and I generally try to do a weekly dinner. Usually, she’ll come over on a Tuesday, I’ll make dinner, we’ll watch a show and that’s that. But since the beginning of this year, I’ve been coaxing her into a few easy gaming experiences.

My first foray started with Balatro to resounding success. I picked Balatro because cards are a familiar concept even to non-gamers. It’s also an easy game to learn how to use a controller with since you don’t have to move a character or manipulate a camera – just focus on learning where the different buttons are. It’s also – despite being a single player game – easy for me to play “with” her as a coach/backseat gamer/adviser when it comes to strategy.

We’ve dabbled in a few other things here and there – even starting up a co-op run of Sea of Stars, a game that I love and know backwards, forwards, and sideways. It’s turn-based and lets her start moving a character in a 2D game.

But other than that, her most recent and relevant gaming experiences are memories of Pac-Man in arcades that have long since shut their doors.

So making the jump to Bananza is actually kind of huge. She hasn’t had to manage both a character and a camera before. She has zero platforming experience. She doesn’t know what a “collectathon” style game is or any of the Nintendo tropes of game design.

So, I wanted to see – could she pick it up and learn it? And this past Tuesday night, we sat down and I put the controller in her hand.

All things considered, it went surprisingly well. I was honestly really worried she wouldn’t even be able to walk the character forward – it can seem strange to those of us who have been gaming our whole lives, but if you ever watch someone try to manipulate a character and a camera in a 3D virtual space for the first time, it can be extremely challenging for them. And that’s before you add in jumping or digging or any other sorts of obstacles.

I’ll also take a quick moment to mention that the camera itself is one of trickier aspects of Bananza that you’ll see as a common point of critique across reviews. Because you can constantly dig yourself into literal holes as you’re moving both laterally and vertically in almost fully destructible environments, the camera has a lot – and often too much – to keep up with in this game. Get yourself into a tight space (which you’ll do frequently) and you’ll end up in pseudo-first-person mode and/or lose sight of DK.

The camera will usually do an okay job of creating transparent enough views to give you a sense of where you are and what’s around you, but it is far from perfect. And my mom found this out the hard way – punching a hole into the ceiling, climbing up into it, and having zero clue of how to get out at first. But after taking a moment to reset, she did get out and we moved on without much incident.

Yes, I was there to offer her a bit of advice in case she was getting lost or frustrated. But mostly, she just punched her way forward – or sometimes down by accident. I also put the game’s Assist mode on for her once she got to the first enemies since in Bananza, it’s more than just an Easy mode that decreases damage or anything like that.

Assist mode actually has a couple of great features – like auto-recovering DK’s health and automatically turning on the navigation help. In Bananza, you can sing by holding down L (left bumper) and music notes will trail in the direction of your objective. With Assist mode on, it’s always there pointing you forward to complement the yellow objective markers.

Watching her play made me even more aware of the smart design choice behind the big, bold yellow text and icons for indicating game progression. It provides great contrast that’s easily visible – especially in a game that has a lot of purples and things of that nature around main quest areas given the color scheming for the antagonists. And while at first it can seem overwhelming to figure out what to punch or how to get to the objective, the environmental use of texture, color, and shapes mostly does a good job of signposting what players should try to interact with.

Did she sail through the intro with a ton of ease? No. But she was collecting gold, punching through environments, climbing walls, and navigating early jump puzzles via barrels and the like. (She really didn’t like the enemies that burrow under the ground and spike up under you though. 0/10 not Ann Marie approved.)

But ultimately, she made it through the intro area and even fought the tutorial “boss” to break through to the Lagoon Layer within just about an hour of playtime. Her vision might not be 20/20, and her gamer skillz might be next to 0, but she was able to pick up the tools the game was giving her and learn how to use them relatively quickly.

So, whether you’re 6 or 64 (aka 38 years young in Mom Math… in case she asks), Bananza seems to have both an approachable and an accessible onboarding experience. Perhaps even more so than other 3D platformers… if that’s even what it really is. Which is to say, I’m segueing to the next part of this review.

3D Platformer? Or 3D Smashformer?

Hear me out: Donkey Kong Bananza is only a “3D platformer” because that’s the easy, common language we have to describe it. But just because something is “easy” that doesn’t make it “accurate.”

Bananza is much more of an adventure game that has elements of platforming and action in it. That’s a much less succinct way to put it, but I’d argue it’s a lot more accurate.

In this “platformer,” the most used button isn’t going to be Jump at the end of the day. By far, it’s going to be Punch.

And while there are sequences of platforming all over the place, some even requiring a good amount of practice and precision to execute, the whole world is a giant sandbox that you can punch your way through to find any number of creative solutions.

You almost never need to follow a prescribed path forward. It’s generally not going to say, “Jump here, then here, then here and the next til done – goal!” Most of the time, you can look at a jump puzzle, go around it, dig through it, or even fly right over it and find a backdoor into any objective. From very early on, I found myself smashing through entire hillsides to find a Banana, only to realize I was behind a concrete wall I was “supposed” to blow up. Whoops. My Banana now.

You can punch your way to almost any objective – and for that reason, I’ve jokingly been calling Bananza a 3D Smashformer.

And consequently, I think it’s even more accessible than most traditional 3D platformers. If you struggle with fine motor controls, you don’t have to master most of the platforming. If you don’t have deep knowledge of 3D platforming norms, you don’t have to worry about your genre inexperience.

The level of player freedom and expression is almost unprecedented. There is no one solution for how to progress the main objective or find most of the game’s hidden collectibles. The level design is a phenomenal achievement that sets a new standard because it holds up even under extreme levels of destructibility.

It lets you think you’re sequence-breaking the game, all the while you’re just making the most of the tools in the toybox that Nintendo’s wizards made for you. You can follow the obvious path or smash your way to a totally different one. So long as you find your way forward to the next Banana and the next, it doesn’t matter how you get there. It’s never a, “Oh no, you had fun wrong” moment. The freedom is simply astounding.

And that’s largely what I mean when I say Bananza is “accessible by design,” but there’s still more to it. The game’s overall visual language is also strong in support of this free player exploration. I already touched on the bright, bold, high contrast color scheming – but the general use of large, simple shapes helps too.

Whether docked or handheld, close or far from the screen, most of the game is visually very approachable. Some things are intentionally hidden of course, but even then there are tools to help the player sniff out the game’s secrets.

First off, there’s DK’s slap that acts like a radar. By hitting the ground, you can send out a shockwave. Not only does this pull in nearby objects like gold, but it also helps highlight hidden collectibles and things you can interact with in the nearby area.

It’s also a skill that you can strengthen over time. I haven’t mentioned it yet, but for every 5 Bananas DK collects, you get a skill point to spend in a skill tree. This makes Bananza’s collectathon that much more rewarding – not only do you get traditional cosmetic unlocks for finding collectibles like new outfits for DK, but you also get mechanical upgrades that improve his gameplay.

One of these upgrades comes in the form of increasingly better radar. Now, while I spammed this feature happily during my 45 hours of collecting every pre-credits Banana, it’s certainly not perfect. I don’t love that the range starts so limited. And even when maxed out, it’s not great at finding things above or behind you – it mostly helps highlight things that are in DK’s general vision cone to begin with.

That said, it does have some decent audio cues to go with the visual highlights of hidden objects. Different things will make different sounds when DK slaps the ground. Fossils (which you spend for DK’s outfits) will emit a hollow, almost metallic twang. Whereas Bananas will give off a more sparkly sound (I apologize for my bad audio descriptors, a sound engineer or artist I am not).

But the audio cues seem to have a similar directional issue, meaning they don’t work as well for objects that are directly above or behind you. The Switch 2 makes a lot of strides over its predecessor, but even with good headphones it doesn’t hold up to Sony’s 3D audio tech in my experience.

Beyond DK’s slap mechanic, the map navigation itself can be really helpful for finding your way to objectives and even the most well-hidden collectibles. As you punch through terrain, there’s a certain RNG chance to find chests. These usually contain gold, but they can also contain maps that will mark undiscovered fossils or Banandium gems (aka Bananas) on your map.

You can also buy these maps and other helpful items from the Stuff Shops in each Layer (aka item shops in each level/world). These cost gold, but will help you clean up any items that you missed while exploring.

Now, let’s talk about the game’s map itself because I’ve seen some split opinions on this. Some people don’t like it – and some people like to point out its frame drops. But me? I love the choice they made here.

In Bananza, when you open your map it’s actually a full 3D render of the world you’re in. It’s basically like if you took the camera and just zoomed way, WAY out – and then were able to freely rotate and manipulate the model to see things you couldn’t before, along with icons that show you where DK is along with any other important locations like your main objective or items you’ve uncovered but not yet collected.

To me, this is much more intuitive and approachable to use than a 2D abstraction where the map is just a flat representation of terrain. Especially in a game that emphasizes verticality as much as this, being able to see in 3D how high up or down something is and not just where it is laterally is crucial for aiding exploration. It helps the player fully visualize the level and may aid with certain cognitive disabilities.

The map is also your way to fast travel. You can freely select any checkpoint or rest spot you’ve unlocked within a Layer to fast travel to at any time. The only real restriction is on fast travel between Layers – which you simply need to use a specific Gong location to move to other Layers instead.

It’s fast, it’s free, and there are no real moments of locking yourself out of going back to find anything that you might have missed. It’s extremely player-friendly in that regard. There’s also a generous autosave plus the ability to manual save any time from the in-game menu – so you don’t ever have to worry about lost progress.

And if you’ll indulge me, I think here is where I want to pause to tell a bit of a personal story that I didn’t really see as an accessibility thing until fairly recently.

Collectathons, Completion, and OCD Triggers

Since moving to BlueSky last year, I’ve slowly been more open when it comes to talking about my OCD. It’s not something I hide, but it’s also not something I advertise – especially online. But it’s something I have to deal with – even when I’m gaming. And since we talk about things like arachnophobia modes within accessibility menus and other cognitive or psychological conditions, I think it’s appropriate to include this here.

Because of my tendency to count and check and correct and fixate, there are certain types of games that I’ll often avoid because I know they’ll trigger my OCD behaviors. High up on the list are things like open world sandboxes and collectathons. Things with tons of points of interest, easy to miss collectibles, and padded out, repetitive task lists. Even if I’m not enjoying the content – especially hours and hours into the game – I will feel compelled to complete it.

Also, I don’t like the directionless freedom that so many other gamers crave. I like my linearity. I like having a finite direction, with a feasible number of pathways to check and things to accomplish. I obsess over missing things that might have cool or important details, and will check, check, check again to see if I overlooked some nook or cranny.

Bananza isn’t a full open world, but it very much is a collectathon with Bananas, Fossils, and music discs to collect. And while there are literally hundreds of these in the game, I was pleasantly relieved to find that the game walks right up to but not over my threshold for OCD triggers.

Now while this was true for me, it won’t be for everyone. But here’s why I think I was okay with it: it all just works. There’s a lot to find in most levels, but the tools you have to find those things work seamlessly. From the maps you can find in treasure chests or buy in shops, to the 3D world map render, to the singing navigation DK and Pauline can team up to do and the free fast travel system that supports it all – you don’t have to worry about locking yourself out of finding things or searching arduously for hours to see what you missed.

The team behind Bananza have crafted a pretty frictionless collectathon experience – and what’s more, none of it is even required to progress. You don’t need a certain number of Bananas or Fossils to unlock the route to the next Layer. Which again, lowers another barrier to accessibility by minimizing the onus on player skill or time investment to have to find and reach some of the trickier spots in each of the Layers.

That’s the bulk of what I wanted to say about Bananza’s inherently accessible game design, but before I can wrap this up – I do need to dig into some major areas where the game could improve, and a lot of that comes down to its limited accessibility options.

Accessibility: Design vs. Options

Back at the start of all this, I dug into how intuitive Bananza’s new player experience is, and how approachable its visual design language is. I even praised how it minimizes the need for a lot of text-based tutorials. It’s a model that generally keeps the player out of menus as much as possible.

But it doesn’t wholly negate the need for those menus – and what Bananza does have available for its system options is fairly limited in scope.

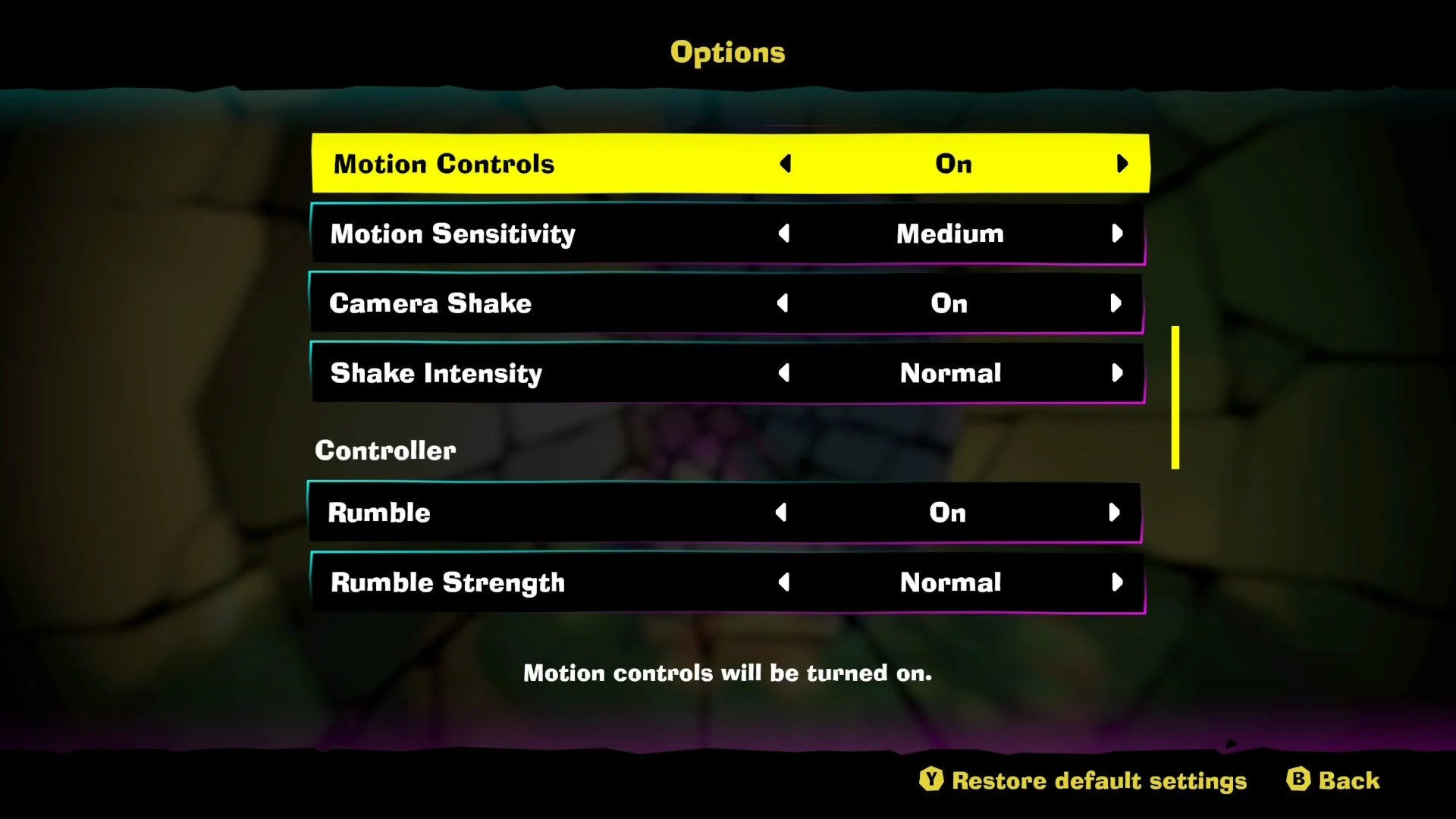

Screen shot of Bananza's system menu, showing options for motion controls, camera shake, and rumble

For example, while the font and text size are generally okay for most players, there isn’t really much in the way of increasing the text size beyond a minimal effect for subtitles. There’s also nothing like a background option for subtitles to help boost the contrast for those instances where there is a lot going on screen, especially in lighter areas.

There’s also no text log, which is something I’d generally like to see in most if not all games. Normally, it’s more necessary in RPGs or narrative-heavy games. But while Bananza isn’t exactly that, there is a particularly strong use case for a text log here anyways: Kongling.

Kongling (or whatever you want to call the language that most of the animals in this game speak) is just a made-up hodgepodge of sounds. Pauline is the only character who speaks English/whatever your preferred language is. So when the other NPCs are talking either during cut scenes or even just giving helpful tidbits about where to go and what to do in the world, you can’t fall back on the game’s audio to help you interpret the dialogue.

Also, a lot of the text auto-advances. Not all, but a good amount. So if you can’t read fast enough or you get distracted by something in your environment, you’re apt to miss something. For all those reasons, it would be great to see a text log that stores something like the last 100 lines of text.

Aside from the in-game text, there are some basic options to modulate the sensitivity of things like the audio, vibration, and camera movement. You can also invert the camera along both the X and Y axis and there is one button input you can swap – but that’s it. You can’t customize the button mapping or control scheme beyond flipping the functionality for the A and B buttons.

By default, B is your down punch and A is your jump – but if you’re used to jump being the B button, it lets you make that one swap. Natively, the idea seems to be DK’s down punch is on B and his upward punch is on X, so the directionality of the face button is meant to be intuitive there. I will also take a moment to mention that I think it’s a smart choice to also have no button input required for climbing – just walking towards a wall will have DK scaling most any surface. One less input to deal with, the better.

But if you need to freely remap controls, you’re not going to find that here. And while there is some mouse mode functionality in the game, it’s not going to really lend itself to a lot of alternative accessibility use cases for getting around using the traditional control pad. I don’t have a whole lot to say about the mouse implementation since it is really only used in minor ways like how a potential Player 2 aims Pauline’s singing attacks.

Editor’s note: Reminder that the Switch 2 enables button remap at the system level but may not update for on-screen prompts in-game and will need to be changed when switching between games

To that end, I also don’t think the 2 player co-op mode overly lends itself to accessibility either, unless you’re okay with being the Player 2 who takes a backseat – riding on DK’s back as Pauline while someone else takes the wheel as Player 1 to control most of the action.

That said, having someone be your Player 2 and using Pauline’s voice to help absolutely demolish enemies might aid you in combat at the very least if you’re having trouble navigating the controls during the game’s action sequences. (And with how tanky that final boss’s healthy pool is… you may need it.) It just won’t help you outside of the battles much when it comes to exploration, navigation, and platforming.

I will say though that the reticle you use to aim for both Pauline’s singing and DK’s throwing attacks is pretty large and easily visible, which is something I critiqued in my accessibility review for Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 – almost positing that it would benefit from options similar to larger text size or background opacity like you see for subtitles.

Helpful items you can buy from the stuff shop to make the gameplay experience easier with added survivability

I’ve gone back and forth over whether Bananza would even need some accessibility options like a High Contrast mode, and largely due to the simple shape language, natively high contrast colors, and the already well sized HUD elements, I lean towards the side of it not being overly necessary in this case.

But there are still some missing options that would be incredibly cool to see like narrated menus along with the other things I already mentioned like a text log, freely remappable controls, and expanded use cases for the mouse mode. I’ll link to the ESA’s tags from their Accessible Game’s Initiative here for anyone curious to peruse as I think it covers a lot of those bases too.

And while I do think Bananza is ultimately a more accessible game than not in many ways, there is a reason why I’d be so passionately invested in seeing Nintendo push the envelope even further here.

Inspiration, Impact, & Visibility

Ultimately, I think Nintendo have laid a solid foundation for game design that is at the very least widely approachable, if not 100% fully accessible. For all the reasons I’ve already stated, Bananza does an amazing job of inviting play from players of all ages and skill levels. It also does a decent job of meeting needs across a number of disabilities as a result of that, but not all.

I think if Nintendo were to go that one step further and add a bit more depth to their accessibility options for visual aids, text sizes, directional audio, and mechanical inputs, it would set a powerful and highly visible standard for other developers to see.

Nintendo games are the kind of experiences that not only inspire and delight players – but other developers too. For decades, people have gotten into game dev because they were inspired by playing Nintendo games. From childhood to adulthood, they are masters of crafting adventures that everyone wants to enjoy and share and celebrate.

So the potential impact that they could have on the standards set for both accessible design and accessibility options cannot be understated.

They aren’t the kind of company to put out a spokesperson or a studio head for us as the audience to get to know like an auteur or celebrity. They won’t make a loud or explicit show of their game dev methods or philosophies.

But the wordless impact of the sheer quality of software they put out? Now that’s earth shaking. And I’m hopeful that we’ll see them take more and more strides that move the world in the years to come on the Switch 2 and beyond.

That’s my take on Donkey Kong Bananza’s accessibility. But now it’s your turn – first of all, thank you if you’ve made it this far. This was a big, chunky monkey of a review. But hopefully it was unlike any other you’ve seen for this game so far – and now I want to hear from you. What do you think of the points I’ve discussed here today? Is there anything that I missed? Please, let us know – let’s keep the conversation going!