Do Games Need Easy Mode to be Accessible?

“What Makes a Game Accessible? Is it Easy Mode?”

“Easy vs. Accessible: What’s the Difference?”

“What Accessibility Features Should be Standard?”

“Do Soulslikes Need an Easy Mode?”

This article doesn’t actually have 5 titles, but what you just read was me struggling to get this headline right. The subject I want to discuss today is a tricky and potentially polarizing one that could get some strong reactions from the headline alone, so I really hope people take the time to read beyond it and see what I have to say.

Anyone who knows me knows that I’m passionate about accessibility, so it’s not unusual for me to spend a lot of time reflecting on a topic like this. But recently, I’ve really tried to push myself to challenge my own assumptions and ask: has my position changed?

I’ve come to realize, the answer is yes. How I would answer the question, “Do games need easy mode to be accessible?” might not be totally different than it was even just a week ago, but the nuance of that answer and the reasonings that go into it have evolved during this exercise.

Traditionally, I’ve always made a point to see multiple sides of the argument since it’s a complex topic on both the developers’ and the players’ sides.

On one hand, the question that comes to mind is “What’s the harm? If easy is just an option, you can choose to use it or ignore it and have the experience YOU want to have.” Other players’ choices are their own and have no bearing on how you want to have fun.

But on the other, I wrestle with the idea of creator intent. What if the developer’s goal is to create a challenging experience that pushes players to strive to succeed by learning how to engage with a game’s systems and conquer its obstacles?

Also, I am not a developer – I have no idea how hard it is to get a game’s balance right so that “normal difficulty” feels “normal” to most players, let alone tailoring that difficulty to include multiple different settings.

Those are the rational arguments in my head. But something else that I’ve had to confront while reflecting on easy mode’s place in accessibility is something less rational and more emotional. Something that I’ve had to admit isn’t a thing I like about myself, and is even a little bit ugly if left unchecked.

I’ve always believed that there’s inherent value in learning how to overcome a challenge. Taking the time to assess what you’re doing, why it’s not working, and how you could adapt. Achieving success under those conditions is a reward that far outweighs any amount of luck or natural skill that isn’t further honed by study, hard work, and practice.

And if I’m being honest, I think that mentality planted a seed of bias in me. It worked great as a student-athlete. But less so as a gamer covering accessibility. When I heard a question like, “do games need easy mode” my kneejerk response was at least in part… no.

But lately I’ve made a concerted effort to really challenge myself on that position. And a big part of what I’ve found that’s pushed me to evolve my stance is this:

Not everyone faces life on a level playing field. My own experience is not universal, so I shouldn’t assume that what applies to me applies to everyone else. To quote a good friend of mine who struggles with his disabilities on a daily basis, he feels like he “lives life on hard mode.”

Different people struggle with things that a lot of us take for granted every single day because the world isn’t made with their challenges in mind. Driving, getting dressed, or even playing a video game – daily life is full of mountains to climb whether you see the steep slope from where you’re standing or not.

And even when the playing field is more level, not everyone derives as much joy as I do from struggling to overcome the challenge – especially in their downtime when work’s been hard, the kids were sick, or it’s just a damn Sunday lounging on the couch with a cup of coffee.

So then why not advocate for game design that makes it a little bit easier for more people to access the joy we all hope to find in our hobbies?

And that’s where I’m at today – hopefully a bit more open-minded about why part of my old answer is unfounded. But it’s still a complex topic, and I’m just one person so I won’t pretend to have all the answers.

I just hope that by sharing my perspective I can help more people see the different sides of the argument and feel more informed so that they can join in this discussion too. By sharing our ideas, we can learn and elevate the conversation so that maybe our voices can help spark innovations in the games we all love.

So with that said, let’s take a step back and ask, what makes a game accessible?

Is a game accessible if it gives you the tools you need to try to win? Or does it need to do more than that and guarantee success?

Personally, I’ve always leaned towards the former: so long as the game offers sufficient tools so that most players can at least try to engage with its systems, then that’s a good baseline for accessibility.

But even then, who’s to say what those tools are? Is one of them an easy mode?

First off, I want to start by saying that easy mode alone is *not* enough for accessibility. A game being “easy” is NOT the same as it being “accessible.”

There are so many factors beyond a game’s difficulty curve that impact its accessibility. For instance:

For blind/low vision players, is the game’s text legible? Does the game have subtitles? Can you increase their size or add a background for contrast? Is there menu narration? Are there sighted assists like an audio tone to alert a player when they’re near an interactable object? How is the default field of view; can you increase it? How big are the objects in the game and how much contrast do its environments have? Would it benefit from a high contrast mode? Do certain puzzles or mechanics rely on color, and are there colorblind mode options?

For deaf/hard of hearing players, do the subtitles include options for full closed captions? Can you display speaker names and even color code them? What is the game’s default audio volume like? Can you change the volume independently for dialogue vs. sound effects vs. music or is it all on one master slider? How many important cues rely on audio like when an enemy alerts to your presence or the timing of incoming attacks?

For cognitive disabilities like dyslexia or memory loss, can you review tutorials at any time? Is recent dialogue saved in a text log that you can review? How complex are the game’s systems, and how well are they explained? Is it the kind of game with a ton of menus and mechanics to keep track of? When you resume a save, does the game offer a story recap anywhere? Can you replay cut scenes?

For motor-disabled players, how complex are the controls? How many buttons do you need to use? Can you freely remap those controls and use them with different types of peripherals? Does the game have QTEs? Does it offer any sort of aim assists? Can a second player help assist with the controls? How sensitive is the camera movement, and what options does the game have for modifying it? How much does the game rely on repetitive button inputs, and can you toggle options for holding vs. pressing certain buttons? Can you adjust the resistance for certain controls that map to triggers?

And those are just things I can think of off the top of my head. That’s not even to mention how easily disabled players can get tired from squinting at a screen all day trying to read small text or even just sitting up for long sessions while fighting fatigue from a chronic illness. In those instances, how easy is it pause, stop, and save a game? Are there autosaves? Can you manually save anytime? Or do you risk losing progress if you need to stop and something causes the game to close before you return?

Then there are all sorts of non-chronic and incidental conditions that can impede a player’s ability to play. Maybe you break one of your fingers and need to change the controls you’d normally use for a game. Maybe your kid starts throwing up in the other room and you need to put the game on hold.

Heck, I haven’t even touched on language barriers, the quality of translations or localization work. Is a game available in your native language? If it’s been translated, are there errors or inconsistencies that could make it harder to understand what different items or mechanics do?

The potential barriers between a player and their ability to engage with a game are numerous, complex, and almost impossible to anticipate. But that’s the task devs face when they’re designing a game – and that’s all on top of trying to make sure their game is fun and cool and unique and functional and commercially sound.

Whenever I review a game or talk about its accessibility, I keep all of this in mind and more. What makes a game accessible to one player vs. another will vary greatly. Understanding that is a herculean task and it’s truly a wonder to me when a dev manages to figure out even half of it.

So while I think I’ve made my point that accessibility is so much more than just difficulty, that doesn’t mean difficulty isn’t still a piece of the puzzle.

A game’s difficulty impacts how hard a player has to concentrate and how much effort they have to exert when trying to succeed. This means that for players with chronic illnesses or any number of conditions that impact their ability to focus, a really hard game can go from a tough mountain to climb to an impenetrable wall.

An easy mode could help alleviate that issue. If the game is more forgiving, players who otherwise wouldn’t be able to progress could find some success.

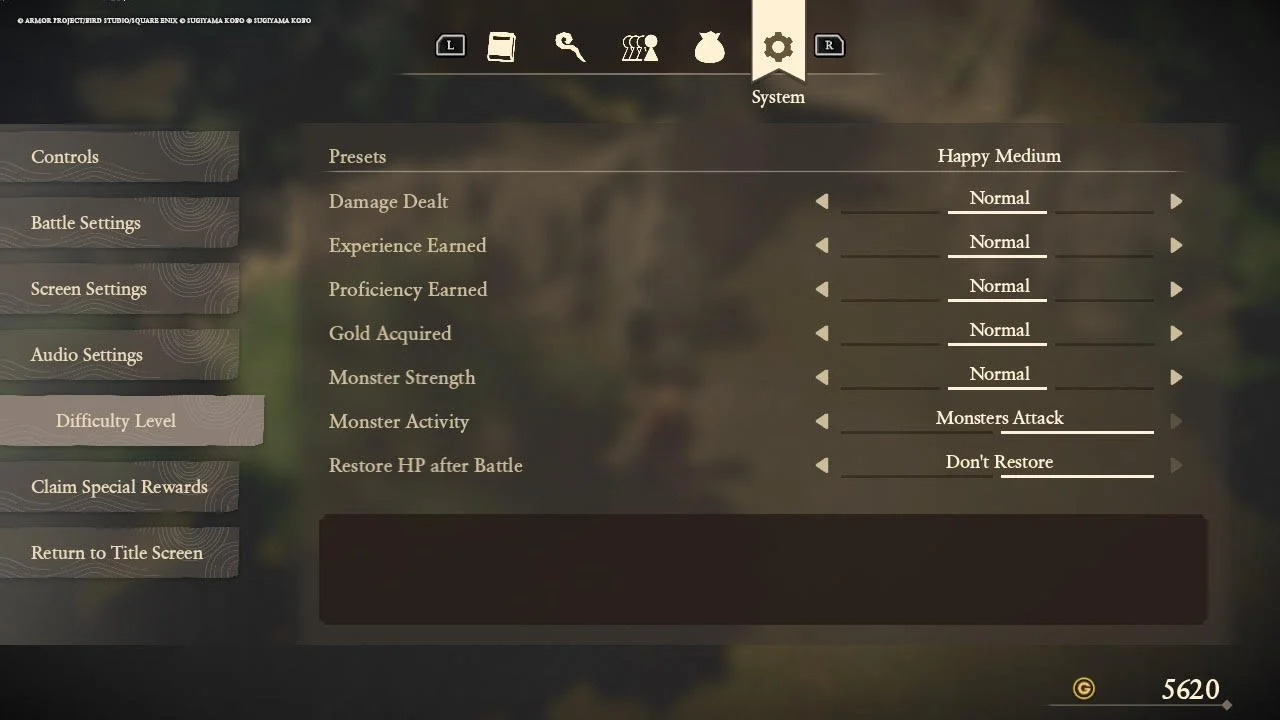

But even then, a flat easy mode isn’t always the best option. Recently, I’ve started to see it become a more common practice for games to go beyond Easy/Normal/Hard and offer options that let players tailor the difficulty of their experience more specifically.

Some games have sliders that let you increase/decrease enemy damage, enemy health, player damage, and even environmental damage. Some games let you tweak the difficulty independently for combat vs. puzzles and exploration – letting you crank up the combat challenge while toning down the puzzles or vice versa. Other games will even go so far as to implement a god mode or invincibility.

Dragon Quest VII Reimagined custom difficulty options

All of these are much more creative solutions than just relying on a flat easy mode, and they can be tailored to suit different genres or specific games. For instance, a traditional easy mode might be effective in most combat-oriented games, but would have less impact on games that are more driven by logic and puzzle solving or tight platforming.

Also, there’s more to a game’s difficulty than just Easy/Normal/Hard settings and assists can come in all different forms. Games that require pointing and shooting often include different types of lock-ons or aim assists. A less obvious example might be something like a turn-based game including indicators for enemy affinities – helping to show and remind players what types of attacks an enemy is weak or resistant to. For RPGs with complex systems, having a good auto-equip option can also help players who struggle to understand how all the different numbers interact.

My point is that so many elements of a game’s core design impact its difficulty beyond just what an easy mode would resolve. And there are more creative ways to let players tailor the difficulty of their experience to suit their needs and preferences than just defaulting to a standard easy mode.

But all that said, easy mode and other assist options are all still tools in the toolbox when it comes to what devs can use to craft an experience that is approachable, enjoyable, and ultimately accessible to players.

While I think I’ve done a good job up til now talking about how and why easy mode plays a role in accessibility, I’ve done a bad job of addressing what inspired me to write this article now.

And that’s Nioh 3.

For those that don’t know me, Nioh is one of those “games that changed me.” In 2017, it was my first attempt at a Soulslike (yes, before even playing an actual Soulsborne game by FromSoftware). I painfully brute forced my way through the game on my first run, without realizing how little I’d actually come to understand its systems.

It wasn’t until a year later in 2018 when I started streaming the game on Twitch that I truly learned what Nioh is. At that point, I found myself amidst a community of deeply passionate and talented players with a genuine desire to share what they’ve learned and help newcomers get better at the game. Because of them, I became a completely different kind of player.

I replayed the game and then did NG+, NG++, NG+++… I think you get the picture. I went from barely scratching the surface of the game’s mechanics to full-on build-crafting and more high-level play. It would still take me years to start feeling real confidence with the genre as a whole, but I quickly became someone who enjoys and understands the inner workings of Soulslikes and other tough action games.

Needless to say, Nioh 3 is a big deal for me. At the time of writing, we’re 3 days post-release and I’m already 38 hours into the game (8 hours from the demo… and 30 from a weekend that involved very little other than playing Nioh 3…).

I LOVE this series, and I am LOVING this game. But just because I love a thing, doesn’t mean I can’t see its faults.

Specifically in this case, none of the Nioh games are what I’d called widely accessible.

First there’s the obvious: these games are hard. That’s what they’re known for. Soulslikes are inherently punishing because of the risk that comes with every death. Enemies reset and you could lose all your hard-earned experience if you can’t recover your “souls” (or in Nioh’s case, Amrita).

But Nioh takes several steps further than that. Nioh’s combat is a lot faster than Dark Souls (especially the older games) and offers infinitely more depth. Both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness is the complexity of its systems. For years I’ve actually called Nioh games Soulslites because they’re as much character action as they are Souls.

These games have extensive skill trees for each different weapon type with dozens of potential combos you can unlock and master. You also equip two melee and two ranged weapons, and can carry a dozen different types of items from healing elixirs to magic talismans and different throwables.

Nioh 3 skill trees menu screen

On top of that, much like in Souls games you have to manage your equipment weight. How heavy your armor is impacts how agile your character is, affecting movement speed and stamina consumption. You have to consider your approach to equipment relative to your character’s build – spending your Amrita to level up various stats when resting at shrines.

While on the surface it’s a similar mechanic to the original Soulsborne games, the names for the different stats in Nioh don’t mean what you’d think they’d mean based on experience with other games in the genre. For example, Stamina affects carrying capacity for equipment, but Heart is the stat that governs your Ki (aka total stamina in combat).

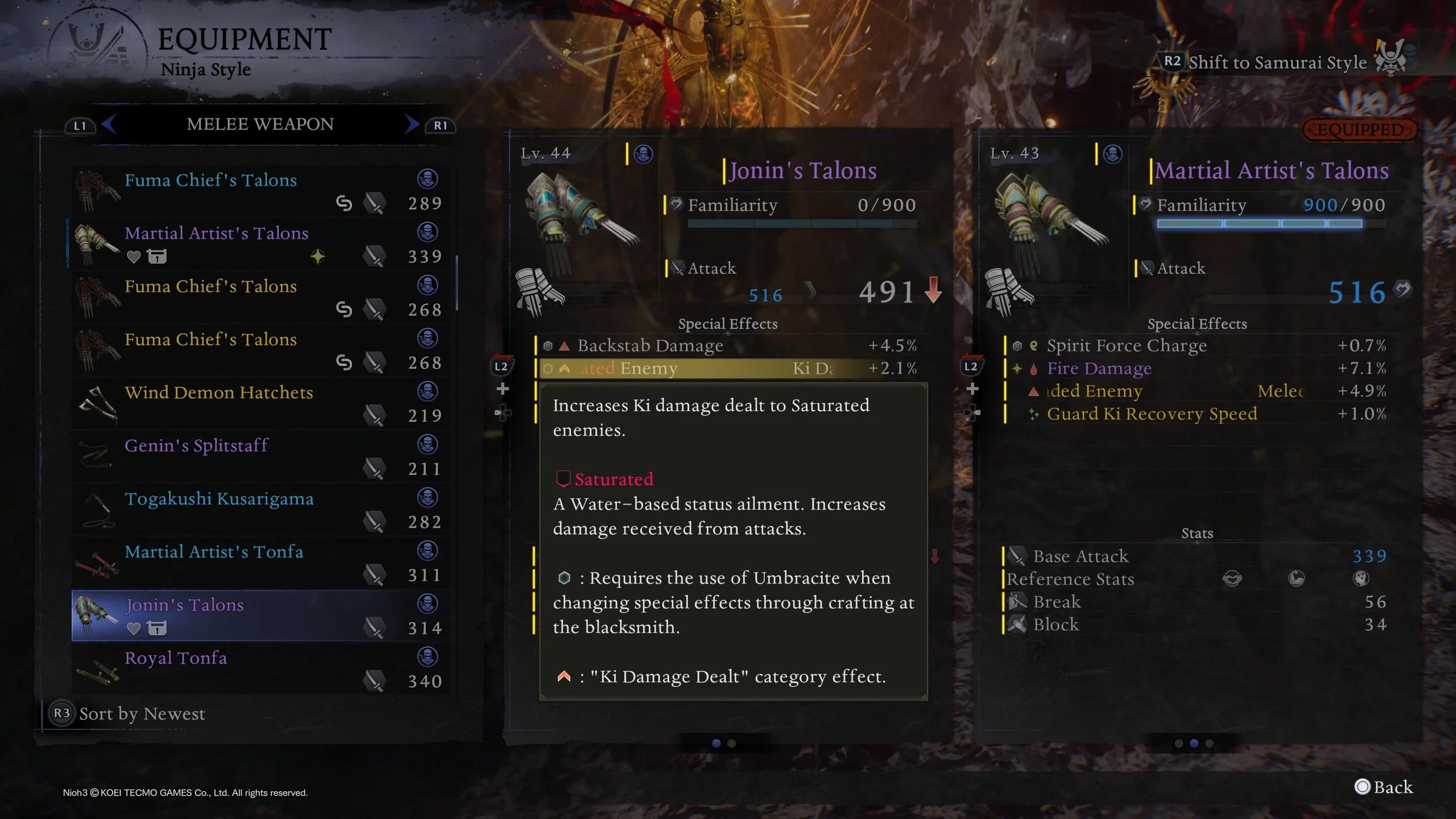

Also, the most common critique of all the Nioh games is the lootpalooza. There is so much loot dropping at any given time and everything has minute stats that would take a year for someone to read through them all. Knowing what to keep and what to ditch or what affects what and how and how much requires a degree unto itself.

Gear comparison screen in Nioh 3 with the tool tip popped out highlighting one of the weapon stats

There are explainers for everything in the menus but it’s almost information overload – Nioh’s menus have menus and I’m not even kidding about that.

On one hand, the amount of information these games offer is great. But there’s really no way to get around just how complex the systems and UI are – hell, even the game’s Pause is a two-button combo. Nioh is a dense game. Period. And each entry in the franchise has only added to the mechanics, giving players more things to learn and master.

For those who are able, it’s incredible – by far it is one of the deepest, most rewarding combat systems and action RPGs I have ever seen. The level of player expression is unmatched within the genre and the things I’ve seen the talented members of the Nioh community do are quite literally mind-boggling.

But for newcomers, even if they’re not coming to the table with things like learning disabilities, dyslexia, arthritis, impaired vision or (insert any number of disabilities here), it’s an incredibly steep learning curve that few will ever truly master. I’ve often said that even more than the challenging combat itself, Nioh’s extensive menus and complex systems are its single greatest barriers to entry.

But I don’t want to say that the Nioh games have *NO* accessibility at all whatsoever so let’s look at what the most recent entry has to offer.

First of all, Nioh 3 continues the series tradition of offering replayable tutorials and even has a dojo that you can go to at any time from a shrine to practice each of the game’s mechanics. That’s a huge step up when you consider the Souls origin of offering almost no explicit tutorials and leaving it up to players to figure things out on their own.

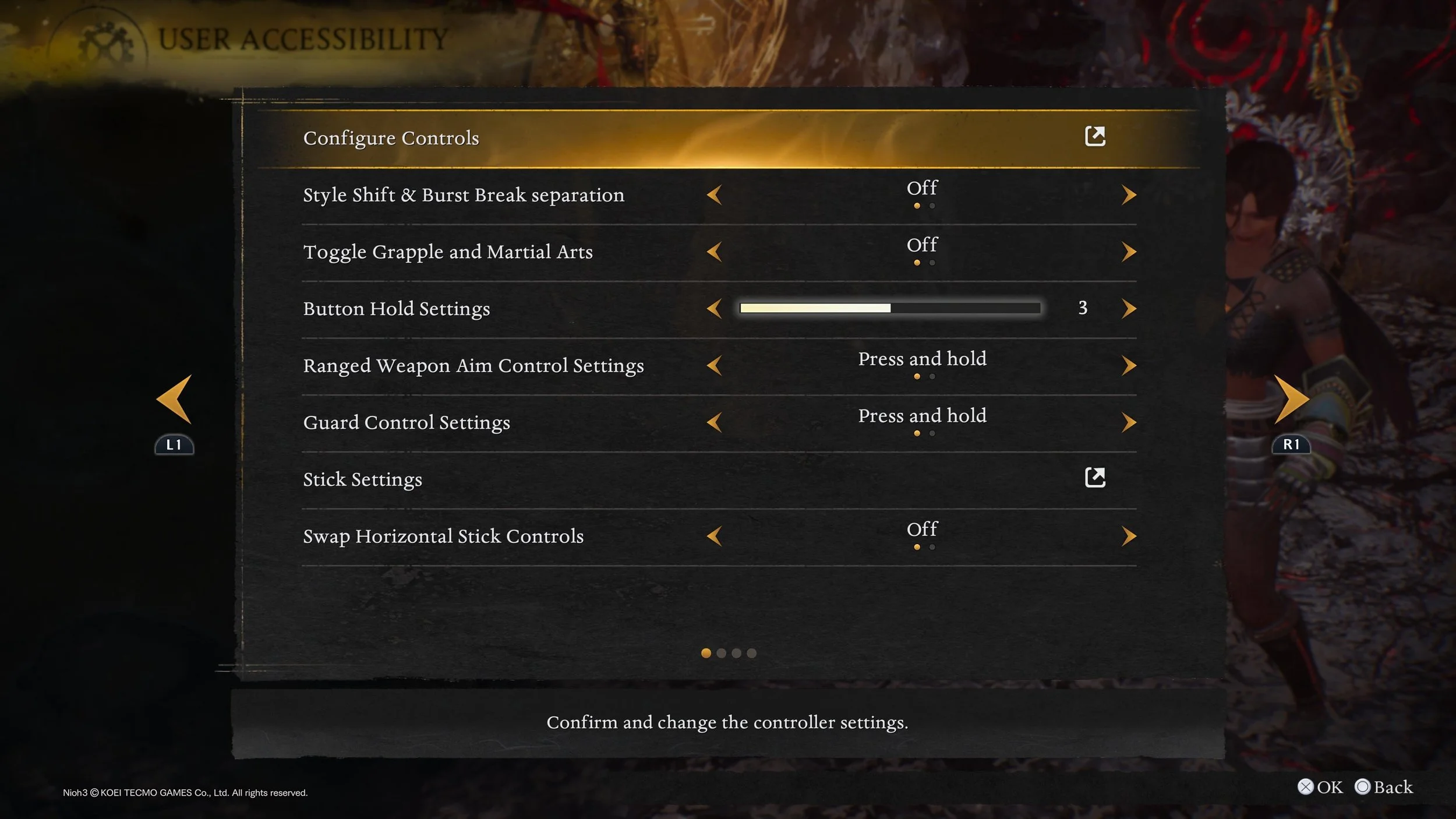

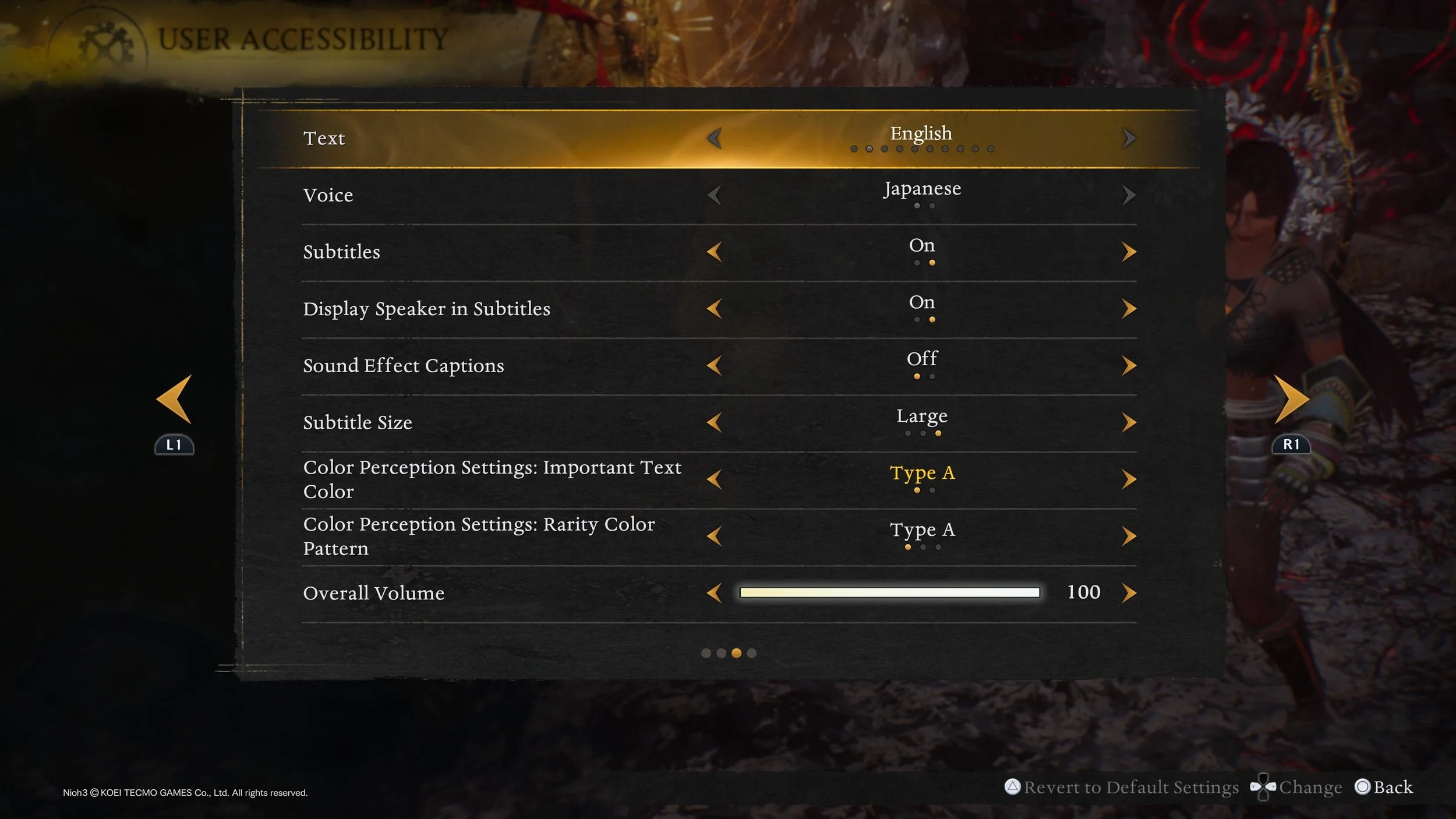

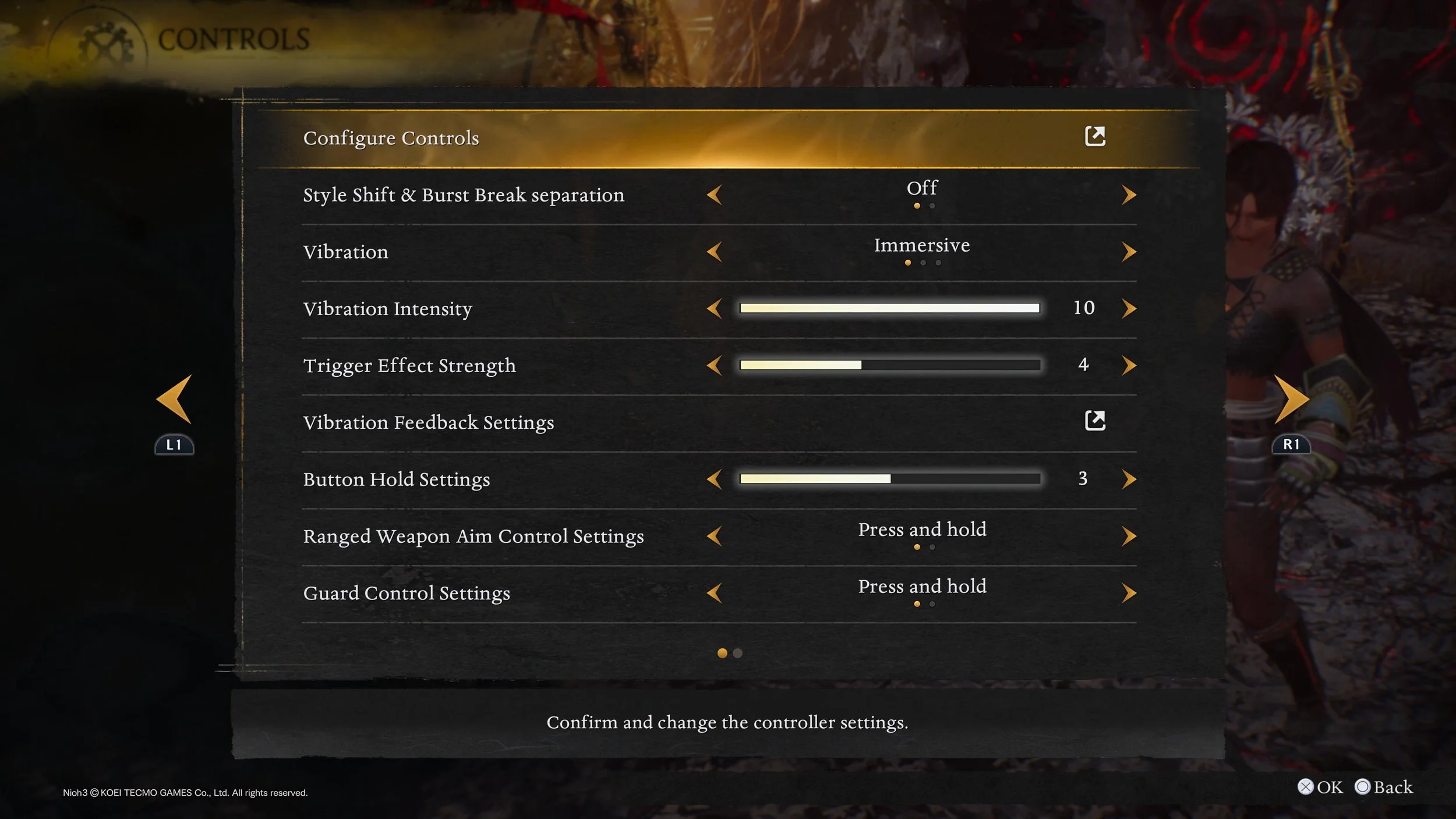

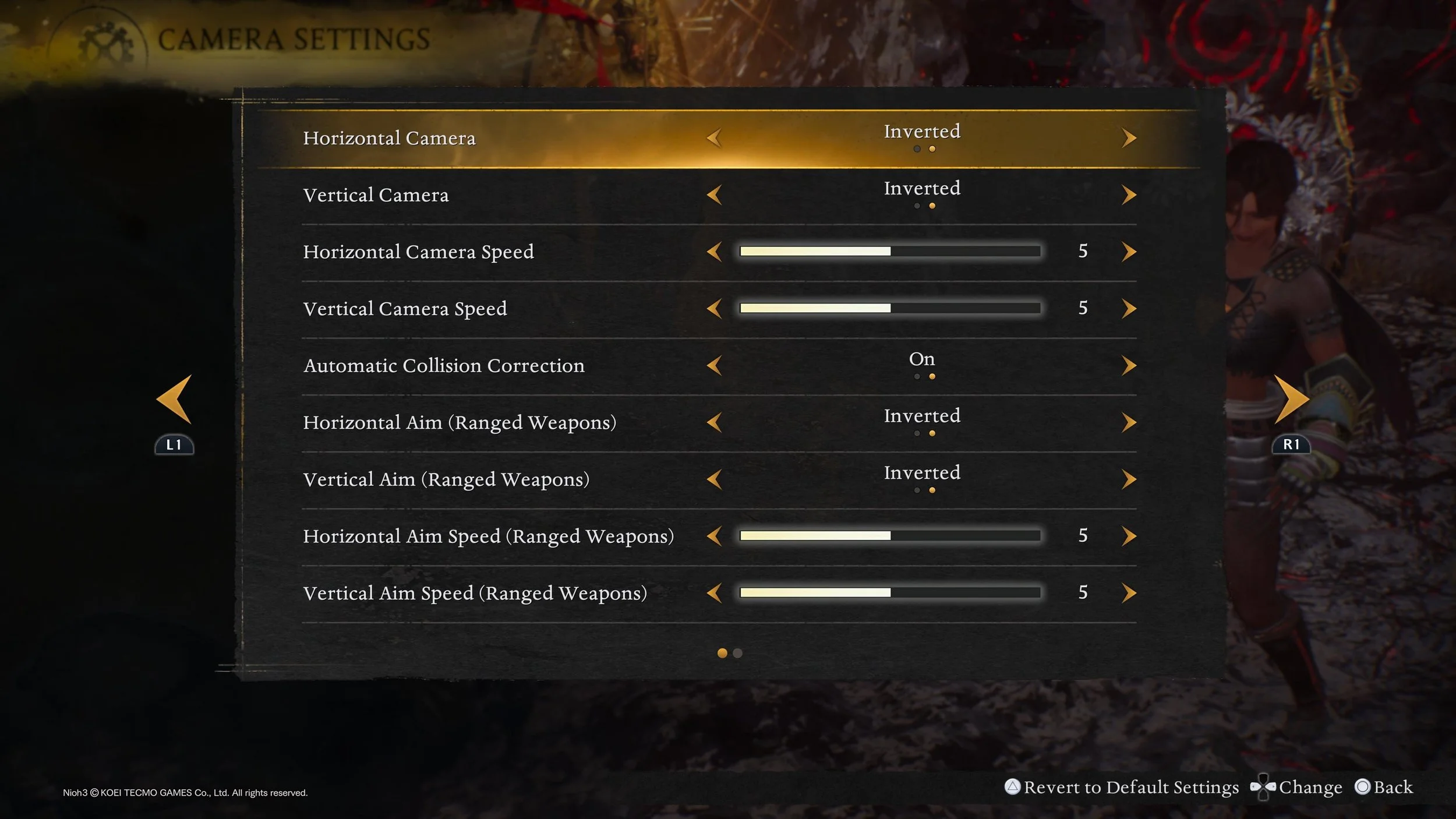

The controls are also deeply customizable – going beyond even just a complete button remap. For example, a new mechanic in Nioh 3 lets you perform a special burst counter when an enemy uses a glowing red attack. The move also switches your character from samurai to ninja style since the game divides the combat into those two archetypes now. But the settings give you the option to decouple the style shift from the burst counter.

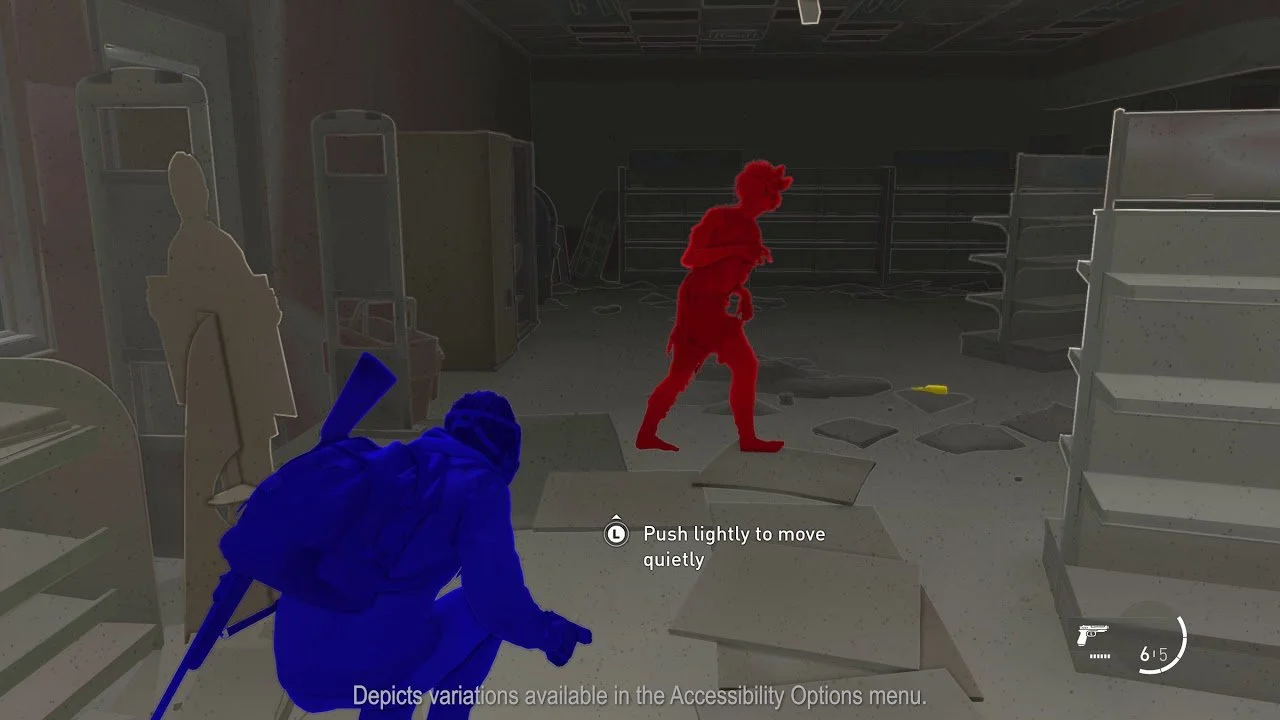

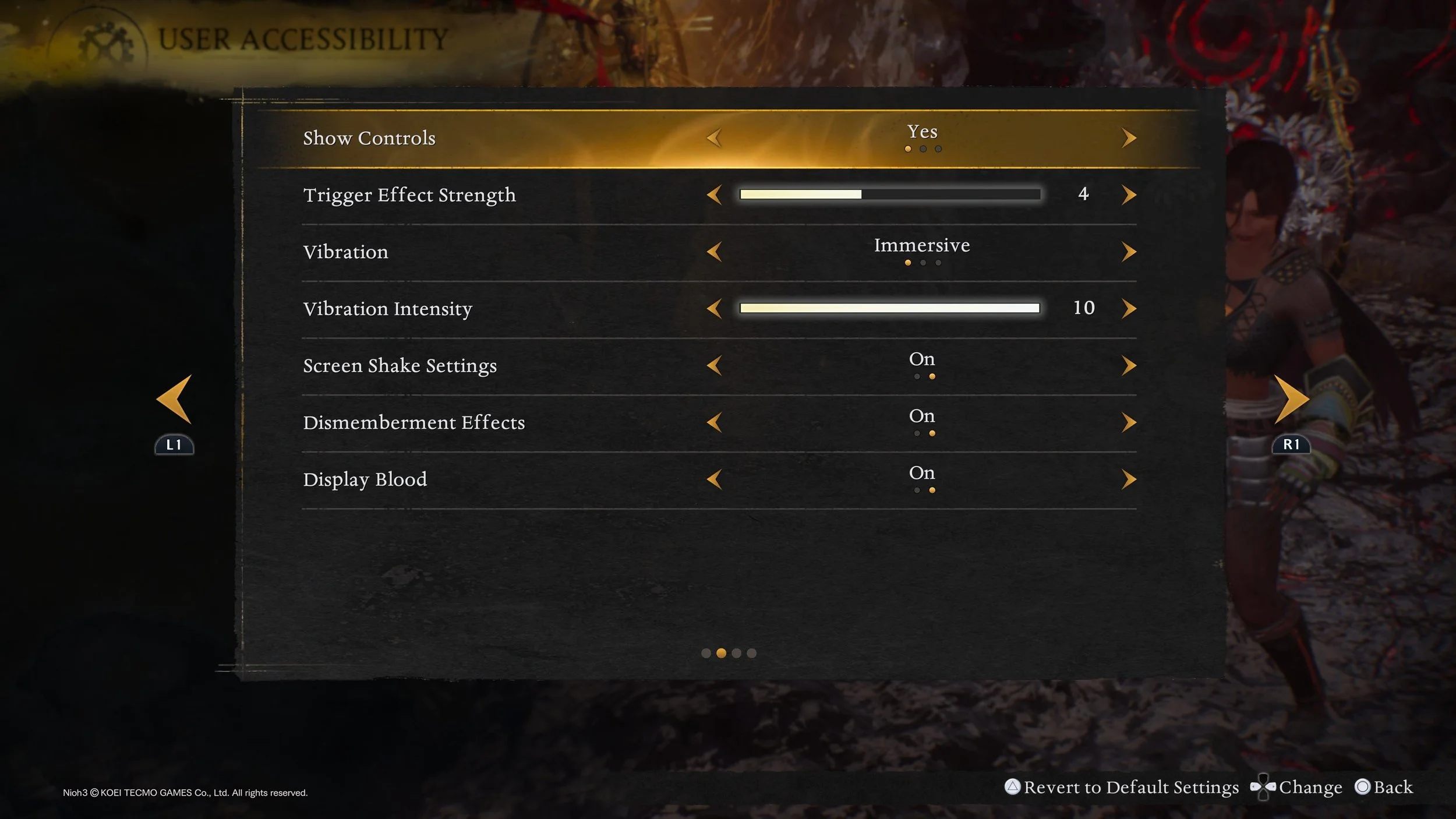

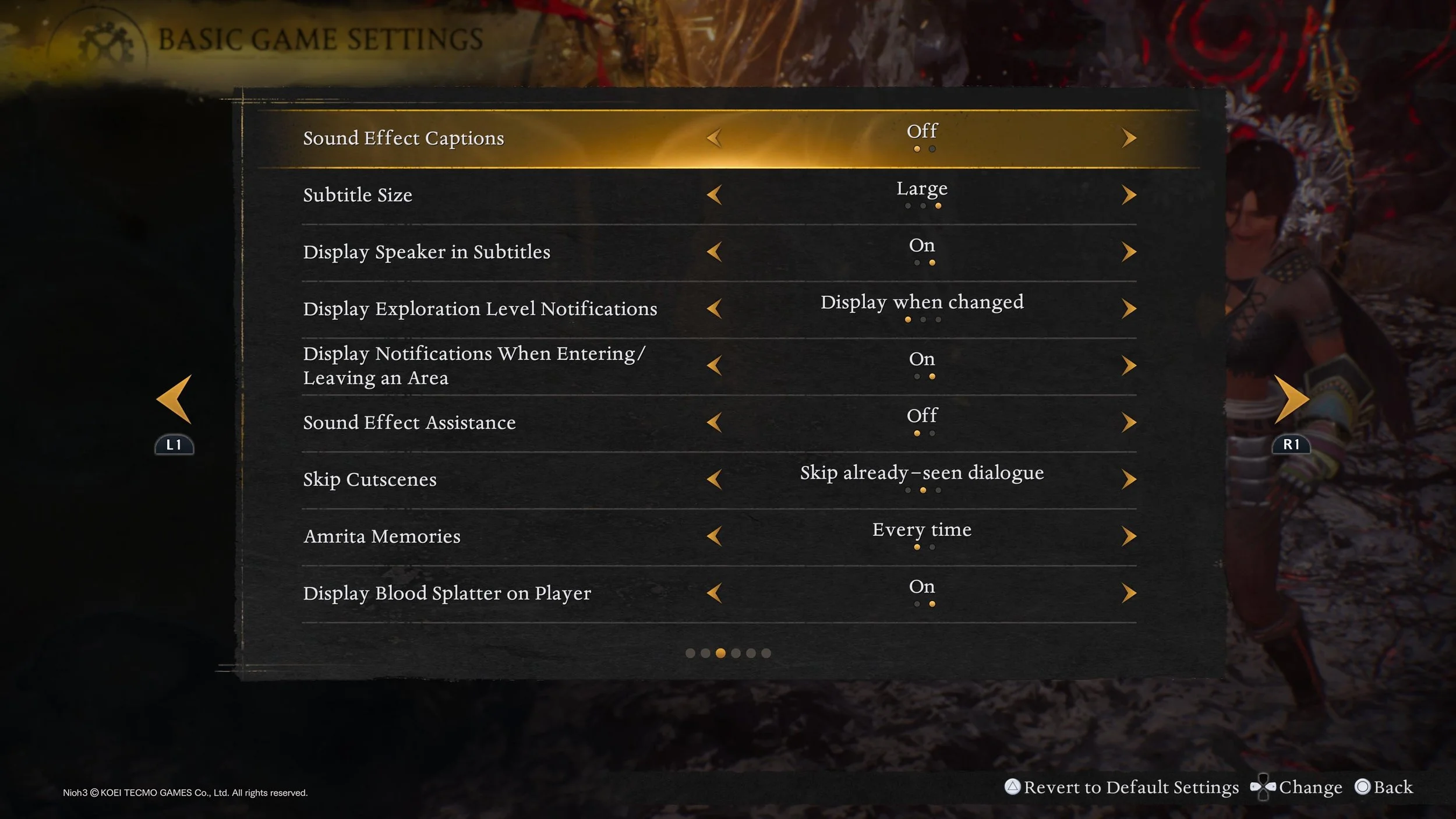

It also has a variety of other options like aim assists and camera inversion. It lets you increase some text size (but not all), change the color code settings for different menu indicators, turn off blood/gore, adjust volume independently for SFX vs. dialogue vs. BGM, and more. It even includes an audio cue you can turn on to alert you when you’re near an item you can interact with – a feature I’ve only seen rarely implemented in other games.

There’s even a dedicated accessibility menu and while it doesn’t offer everything some players would need, it offers a lot more than what I’ve seen in several of its genre peers so I want to recognize and encourage that.

Nioh 3’s shrine menu, showing the level up screen as well as other features like co-op

While some options are missing that would sorely help (like backgrounds for subtitles or a high contrast mode), beyond just the system settings there are aspects of Nioh 3’s core design that lend themselves to accessibility too.

Co-op is widely available throughout the game and comes in multiple forms. You can summon another player into your game for assistance or you can summon an AI-controlled character from a player’s grave. Also, as an open world game – a first for the franchise – it’s easier than ever to go off in different directions and level up. Get stuck in one area? Try going somewhere else to see if there are fights you can win, experience you can gain, and gear you can level up.

Shrines automatically register as fast travel points that you can use anytime by opening the world map, letting you backtrack, level up, save, or respec your character freely so long as you’re not currently in combat.

Nioh 3’s open world activities all pay back into helping the player. Completing activities levels up your exploration, helping to reveal more points of interest on your map that may contain things like Kodama or Jizo statues that enable you to unlock boons like a higher drop rate for healing items or increased damage bonuses in Crucibles, the game’s toughest combat arenas.

Nioh 3’s map menu

But while Nioh 3 offers players a ton of ways to tackle the challenges of its world, ultimately tackle them you must. There is no way to get around combat entirely, and eventually you will have to confront some extremely tough bosses.

And even though the game gives you so many different tools to try to succeed, one of them is not an easy mode or equivalent options for altering enemy damage, health, etc.

For a lot of players, the accessibility offered without an easier difficulty will be enough to at least try and make some progress in the game. But for some it won’t be – and that leads me to ask:

What is considered “enough” for a game to be accessible?

Which tools are considered basic necessities for a standard baseline of accessibility? What kinds of players do you have to consider for establishing that baseline? Who gets to decide what the standards are across developers, players, and reviewers? And does the baseline need to vary genre by genre?

I ask that last part because the game I’ve been talking about is a Soulslike – a genre that’s known for its difficulty and has been the subject of a lot of “easy mode” related discussions.

But what if we did a couple thought experiments and changed the genre of the game in question?

Thought Experiment #1: Horror

Instead of a Soulslike and easy mode, let’s change the game we’re talking about to a horror survival action game with jump scares and a high amount of gore. A good example would be Resident Evil since that’s top of mind right now with RE9 just around the corner.

I have personally tried to play these kinds of games before (usually with and under duress from friends). And even amongst friends with the lights on and the knowledge that it’s all fiction, I find that I’m physically and emotionally incapable of playing these types of horror games.

The jump scares do not interact well with my anxiety, and prolonged engagement with horror content makes me start to physically shake. I don’t care if it makes me seem like a coward because I want to be honest. My ears will ring, I’ll feel my heartbeat pounding in my head, and I won’t be able to calm down without some serious time and distance from the material.

I also don’t handle “realistic” gore well at all. It makes me nauseous and I’m pretty squeamish so I’ll generally look away from explicit scenes in anything that I’m playing or even watching, horror or otherwise. I would not be able to look at the screen for most of an attempt to play something like RE9.

All that said, do I think we should expect or require a game like that to include warnings before jump scares and a no gore/blood mode?

Instinctively, my own answer to that is no. If the devs had those things in mind while making the game then that’s all well and good, but I don’t feel like I would require them to add it. In this case, it would almost feel like an act of censorship since the regulation affects the content.

A horror game is meant to be scary and gross. It intentionally creates that sense of discomfort. While it doesn’t work for me, for others they enjoy the thrill and may even get a sense of catharsis by surviving through that simulated experience.

People know what they come to a certain genre for. In this case, they come to a horror game to be scared. It’s not a one-to-one comparison, but can the same be said of Soulslikes and the challenge they offer? Is it okay for them to be difficult on purpose since that’s part of the appeal to the audience, even if that potentially excludes some people from being able to engage with them?

To explore the genre question further, let’s flip the script again.

Thought Experiment #2: Cozy games, Idle games, Auto-battlers

In the complete opposite direction, let’s talk about cozy games and idle/auto-battlers. Where Soulslike and horror games have high barriers to entry, these games have very few. They’re generally intended to help audiences relax, unwind, and find that sense of carefree enjoyment that might be sparse elsewhere in the stressful world of our daily lives.

So it seems extremely weird to ask – but in the same way we might call for tough action games to have easy mode, would we ever ask for cozy or idle games to have hard mode?

The answer is no. There’s a reason why Sekiro sparks headlines when paired with the words “easy mode,” but there aren’t any clickbait articles trending around Nightmare Difficulty in Animal Crossing (although maybe we shouldn’t give Tom Nook any ideas…).

Easy mode increases access rather than restricts it. But unfortunately, the conversation becomes an exercise in gatekeeping rather than helping prospective players. How one person has fun doesn’t have to match another’s – but that’s what seems to be the result in some of the arguments I’ve seen online when ego gets involved.

Emotional reactions aside, another factor you can’t deny though is genre expectations. Audiences know what they’re looking for when they choose to buy a cozy game vs. a Soulslike. They generally aren’t in it for the extreme difficulty. As a result, we don’t challenge the developer’s intent of making a relaxing, colorful escape from the world.

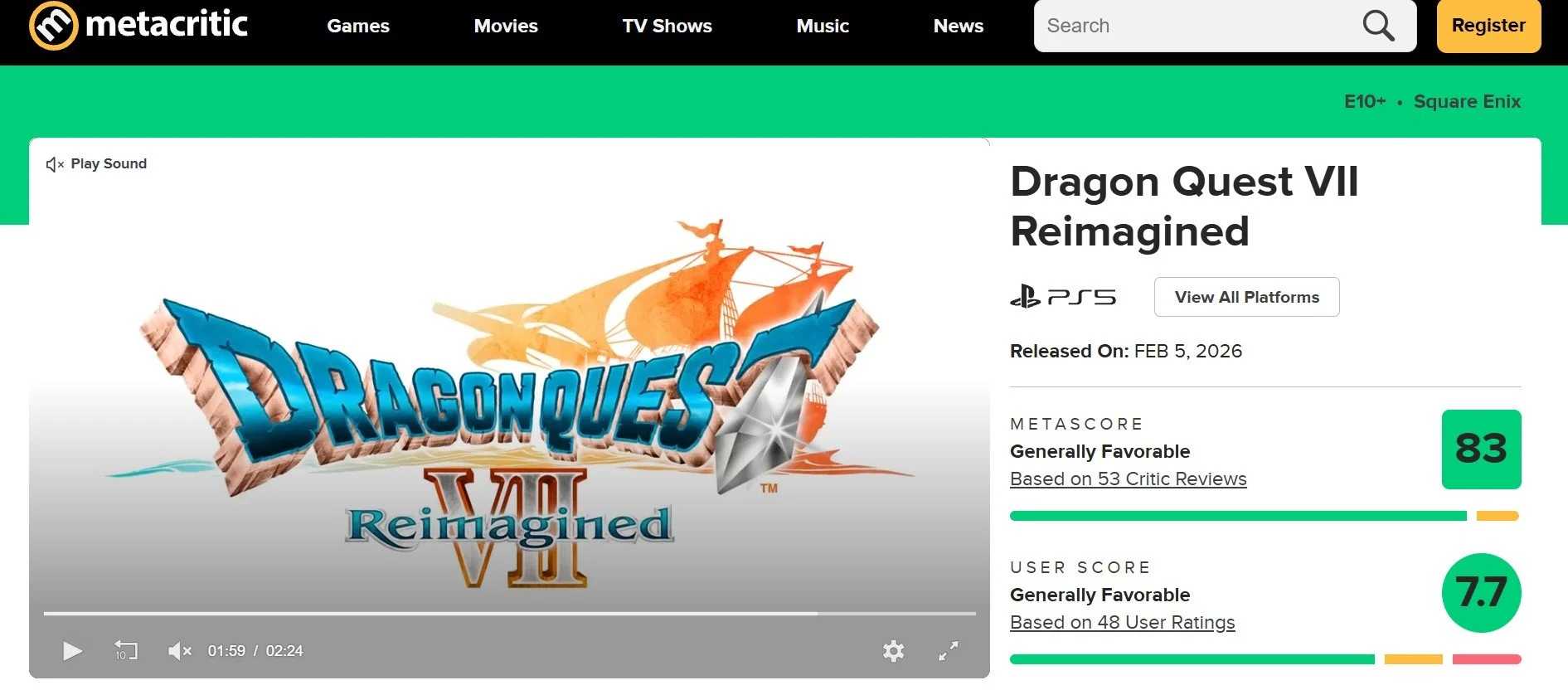

But a recent example of where genre expectations didn’t quite match a game’s reality that got me thinking was Dragon Quest VII Reimagined. Dragon Quest is about as classic as JRPGs get with 40 years of history, helping to found and shape the genre at its core.

While the series sports bright and colorful art styles, the difficulty curve hasn’t always been quite so cheery. Even in the recent HD2D remakes for Dragon Quest I-III, players can run into a wall where they need to grind to overcome tough difficulty spikes. There’s even a decent chance of getting one-shot by insta-kill spells.

But in the series’ latest outing with the DQVII remake, the most common criticism amongst reviewers was that the game is too easy now. On one hand, it’s great that DQVII Reimagined has introduced some new difficulty features to the franchise for the first time – going beyond the usual easy/normal/hard modes to include things like the ability to change how much damage you deal or how much EXP you receive.

But on the other, some of the updates in the remake aren’t optional and they do mitigate the challenge that many classic JRPG fans are accustomed to. For example, characters that fall in battle revive afterwards with 1HP – but previously, DQ is famous for having coffins dragging around behind you with dead party members until you revive them at a church.

Also, enemy weaknesses and resistances are revealed by default. When you select a skill in combat, an indicator will appear over enemies that shows if they’re weak to or resistant against the move you intend to use. That is GREAT quality of life – but there’s no way to change it. Traditionally, a feature like this when implemented in other JRPGs would require you to discover enemy affinities by striking them first rather than revealing them the moment you encounter a monster in battle.

So the trick I think DQVII missed isn’t the addition of easier difficult options – but rather equal options that let you modify the new features to preserve more of the original challenge that traditional JRPG fans enjoy. Yes, there’s a hard mode – but no way to turn off new elements of the design like the ones I described above.

Part of what got me thinking about this was Kinda Funny’s review of DQVII Reimagined. In that review, Greg Miller likened DQVII to a Saturday morning cartoon – something cozy you flip on and don’t need to think too hard about while you have your breakfast or a cup of coffee.

And there’s the rub – on the surface, DQVII isn’t primarily a “cozy” game – it’s a JRPG. Sure, the tone has always been cozy-adjacent because of the art style and humor inherent to the series, but as a JRPG it’s still known for having a challenge, calling for a bit of grinding, and even housing a difficulty spike or two.

So when the game didn’t one-to-one adhere to those genre expectations, it led to some friction and divisive reception over the criticism in the reviews calling the game “too easy.”

Do I think those reviews are wrong? No, absolutely not. So long as a reviewer gives honest feedback about their personal experience with a game, then it can’t be wrong – even if it’s not something you’d personally agree with.

Reflecting on your experience with a game, what about it you liked or didn’t like, why certain things worked for you or not – and practicing how to articulate those thoughts leads to stronger review conversations. Everyone is going to have different perspectives and experiences based on their likes and dislikes, as well as their natural affinities and capabilities – which will inherently be more restricted for some players than others.

I’ll wrap this up by posing a final question:

Does every game need to be for every gamer?

As a matter of appeal, no. We all have different things we like or dislike, and even go through times when we just want certain types of experiences over others.

But as a matter of accessibility? That’s where it becomes a harder question to answer.

On one hand, in an ideal world I’d like to say yes. Every game should be at least accessible to any player who wants to try it.

But the world is more complicated than that – how do you determine which tools are the necessary ones for every player to engage with a game? How do you account for that when you’re building the initial concept for your game? What happens if you realize after the fact that certain aspects of your design make it unexpectedly difficult for some people to play?

And even in an ideal world with all the tools and tech and talent and knowledge to anticipate and account for the whole spectrum of accessibility needs, there’s still the question of creator intent. What if a creator wants to set out to make a really challenging game?

Something I’ve recently added to my own argument with that though is the question of who determines what “challenging” is. My normal might be someone else’s hard, so I need to step outside of my own life experience and remember that too.

My point in saying all this is that it’s a complicated question with no easy answers – which is why I don’t pretend to offer one right answer here today. I honestly struggled with whether I wanted to even try to tackle this subject and post this article publicly because I know how sensitive this topic can be.

But that’s ultimately the reason why I committed to doing this.

I forced myself to do some uncomfortable reflection and confront my own assumptions. I shifted my own ego on the value I attach to overcoming a challenge, and reassessed where the bar for that challenge is set for people living in circumstances that are different than my own.

I wrote the outline for this article not one but THREE times. I spent days writing and re-writing it in my head, drafting it on paper, and then ultimately penning it to this virtual page.

Why?

Because this is a discussion that NEEDS to happen. More people need to talk about accessibility and raise awareness. People need to take on the challenge of seeing perspectives other than their own. We need to share our experiences and learn how to have constructive conversations around how we review games so that it doesn’t devolve into egotism, gatekeeping, othering, and infighting.

The only way to help push our medium forward and help move the needle for innovation is by learning how to share our honest feedback with one another as a community. Players need to help other players learn how to see each other’s points of view. They need to help developers understand what works or doesn’t for them in their games.

We all need to approach criticism in a manner that is positive and constructive, rather than callous and destructive. And we need to learn how to lead with empathy and compassion in a world that seems to lack both those things of late.

So do games need easy mode to be accessible? It’s a complicated question. Let’s talk about it.

Key Takeaways:

“Easy” is not the same as “accessible” since difficulty is just one of many factors that impact a game’s accessibility

Accessibility pertains to a game’s visuals, audio, controls, UI, and many other core elements of its design

Easy mode alone isn’t enough, but it can still be one of the tools that makes games more accessible

Easy mode’s effectiveness varies by genre, so more creative solutions than just Easy/Normal/Hard can be better suited to different types of games

Game development is hard and getting the “normal” difficulty balance just right for most players is its own challenge

Establishing a baseline of what is accessible is a massive undertaking since different players will have different types and levels of accessibility needs

While the hope is never to be exclusionary, there’s still merit to the idea of creative freedom and developer intent

Audiences come to different genres with different expectations in mind

When developers strive to improve in response to feedback, innovation happens – so reviewers and gamers alike should practice thoughtful, constructive criticism

Be kind to your fellow gamers, be willing to see perspectives other than your own, and help spread awareness by being a part of the accessibility discussion